Tag: game designer

Getting Started in Game Design por Joe Slack (uma palestra em video)

Ontem assisti a um seminário/palestra acerca de Game Desing focado em board games, mas que tem vários pontos em comum com os jogos digitais. Foi uma palestra bastante interessante e com algumas dicas sobre o que se passa e como se resolvem determinadas situações. Para além destas informações, o Joe Slack também partilhou outras informações que valem a pena ser revistas. O vídeo foi disponibilizado online..

+infos(oficial): https://boardgamedesigncourse.com/

+infos(o video): LINK

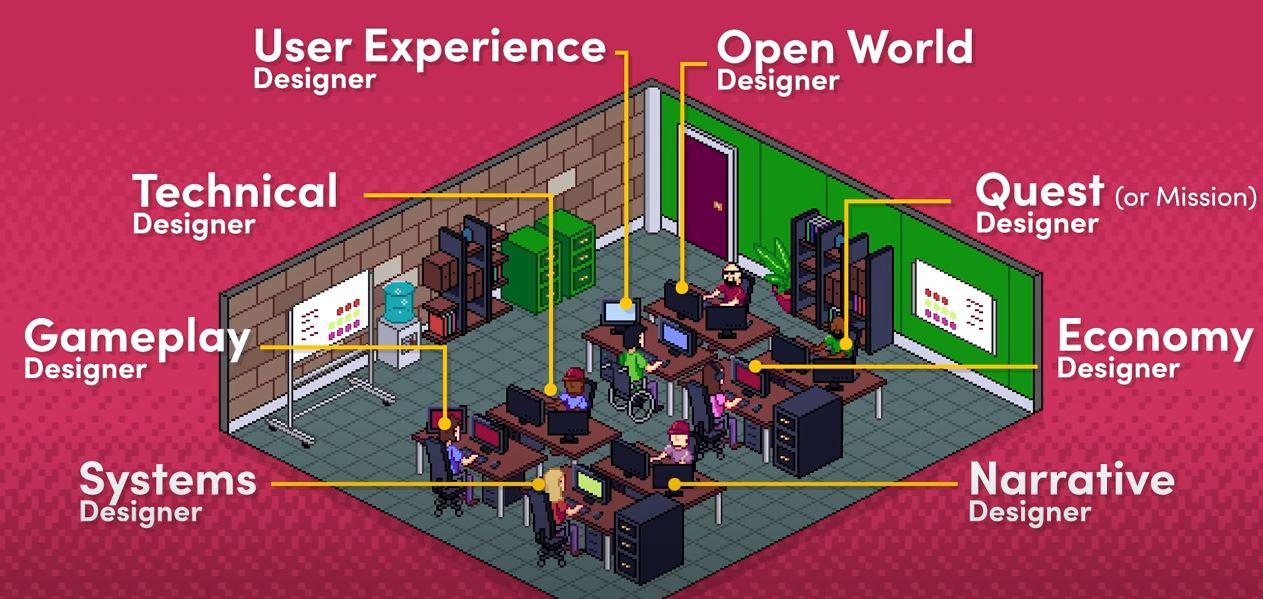

Game designer explicado..

A quantidade de trabalhos/tarefas que envolvem o Game designer.. e que eles realmente fazem :)

Um vídeo interessante que explica de forma rápida as tarefas que cada um faz: o game designer, level designer..

as tarefas/qualidades:

mas no final o que conta é o que já foi feito, o portefólio, mesmo que seja constituído apenas por coisas pequenas!!!

Play Like a Game Designer por Alexey Shkorkin

“Play Like a Game Designer

According to the authors of books and articles, it means you should play as much as possible. Play games in various genres. Don’t just play good games, but bad games too. Do everything you can to improve your gaming literacy.

There’s nothing wrong with improving your gaming literacy, but for some reason, it’s not obvious to everyone that literacy alone isn’t enough. You need to not just consume games, but take a critical approach to them as well.

The results of your critical analysis could take the form of an article or video about how the developers met certain objectives in the game.

1. PREPARATORY PHASE

What to do

1. Play the game. This might seem like an obvious requirement, but our main goal here isn’t to spend a few hours in front of the screen, but rather to examine all the aspects of the game from various perspectives in order to develop as objective feedback as possible.

a. It’s best to beat the game — as long as the game is beatable, that is. If it takes dozens of hours to beat the game, you need to at least finish the main storyline.

b. If the game features asymmetrical gameplay (as in StarCraft, for example) with various strategies, you need to play as various factions and against various opponents.

c. If the game has various difficulty levels, try playing them all.

d. If the game has various modes (single-player, multi-player, etc.), it’s preferable to try all of them. The same goes for board games — play with various configurations and with various numbers of players.

2. Your primary goal is not to have fun playing the game, but rather to make observations that you will then use to perform an analysis. There are no requirements for how to take notes on your observations — just make sure they’re easy to work with.

Try to focus on establishing a connection between design solutions and gameplay:

which solution was implemented

how this was reflected in the gameplay

which in-game resources were employed in order to achieve this

which goal was accomplished by doing so.

These solutions could reside in various aspects of the game, including interface, graphics, sound, balance, controls, game components, etc.

3. You should also take notes of your personal impressions. They won’t have a place in a critical article, but they could influence your thoughts on how a given solution affects the player’s experience.

Jot your impressions down in the form of a “developer’s solution — your reaction” pairing, e.g. “No rally point for trained units — irritating.”

What not to do

1. Don’t read previews and reviews of the game until you’ve played it yourself and written the first draft of your article. First of all, you probably won’t get anything useful out of reading that stuff (you’re more likely to find advertising, emotions, spoilers, unfounded judgments, and useless details). Second, other people’s opinions will just ruin your focus.

2. Don’t rush into your analysis until you’ve completed all the steps listed under “Play the game.” There’s a good chance that you’ll see the game in a whole new light during the later stages, and then you’ll either have to rewrite the whole thing (which will take up time) or just you won’t be in the mood to redo your work (which will hurt the quality of your work).

3. Make sure you take notes and don’t just rely on your memory. You run the risk of completely forgetting certain factors or wasting time looking for them in the game in order to pin down the details.

4. Don’t mistake the rough draft of your article for a complete analysis and publish it before it’s ready. Follow the recommendations from the next phase first.

2. ANALYZING THE GAME AND WRITING YOUR ARTICLE

What to do

1. During the preparatory phase, you identified the connections between design solutions and gameplay. Now you need to organize these connections and flesh them out. If you need to play for a while before you can do this, go ahead and play. The results could take the form of connections such as:

The game has no “fog of war.” This reduces the amount of information hidden from the player and increases the amount of time it takes to get ready to attack the enemy, which in turn increases the importance of scouting.

2. Identify the objectives the developer set for themselves (this is easier to do after doing some work with the connections you found in the previous step). Determine how these objectives were met (or not entirely met) and what was employed in order to achieve this. If the results aren’t clear, spell them out. Try to describe the objectives that were met in such a way that the solutions are reproducible. For example:

Objective: simplify the process of translating and localizing the game.

How this was done: the game has no voice-over — the words in the dialogs are replaced with incomprehensible gibberish, so all that had to be translated was the subtitles and the interface; there is no text in the game world.

Result: the game was released in ten languages simultaneously.

3. If there’s anything else in the game that demands your attention (e.g. a new mechanic, a surprising solution), identify it.

The same goes for elements you liked and for which you were unable to identify an objective or function — set these notes aside; they might come in handy later on.

4. If you have any recommendations on how the game could be improved, they should be specific and well-founded.

a. Specific recommendations are those that describe HOW to solve a problem — instead of “I’d readjust the weapon balance,” write about how you would change the attributes of a certain item.

b. Well-founded recommendations are those that clearly explain WHY a given solution should be changed. When developing well-founded suggestions, it’s best to refer to similar solutions in other games, and not just talk off the cuff.

5. Recommendations for the layout of the article:

a. Identify the developer, publisher, year of release, genre, and platform.

b. Provide a link to a gameplay trailer for readers who haven’t played the game — this will save them time, and they’ll appreciate it.

c. Provide visual aids in the form of screenshots from the game. Sometimes it’s better to make a gif.

d. SPOILER ALERT: warn about spoilers, and hide text containing spoilers.

e. If, despite these recommendations, you decide to talk about your impressions of the game, set them aside visually in such a way that they are distinct from the main text of the article.

What not to do

Here are some typical mistakes that occur when the author of an analytical article mixes their criticism up with something else.

1. Don’t assign the game a rating, and don’t evaluate its various aspects (e.g. 3 for graphics, 4 for gameplay). First of all, ratings aren’t very informative, and second, your goal is not to compare the game to other games. The quality of critical analysis and the quality of the game itself usually have very little to do with each other. The usefulness of analysis is determined by how much the reader can learn from it, and listing specific mistakes in an unsuccessful game can be more valuable than an emotional, praise-filled 10/10 review.

2. Don’t express your emotions. If you can’t stop yourself from providing an emotional evaluation of a certain solution, at least try to provide a logical basis for your point of view.

3. Don’t recapitulate the storyline. Describing the storyline usually isn’t very valuable to script-writers. It would be better to point out interesting storyline developments and how the storyline affects the gameplay.

4. Don’t recapitulate the rules (if we’re talking about a board game). A critical analysis isn’t a tutorial! Try to focus on how certain rules affect the way the game is played.

5. Avoid superfluous details, especially when describing mechanics. A critique isn’t the same as an exhaustive breakdown! A detailed examination of a jump mechanic could be important when analyzing a platformer, but for games in which this isn’t a key mechanic, it probably isn’t worthwhile. If your analysis includes mathematical formulas or lines of code, you’re probably on the wrong track.

3. WHAT YOU CAN GET AS A RESULT

Your result can be something like this. Here’s part of my analysis of Firewatch, with no spoilers or superfluous details.

This is an analysis of a video game, but you can do the same thing with a board game. Board games are typically a little more difficult to analyze, since, first of all, they’re usually more expensive, and second, they’re physical objects (you need to go to the store and buy them, then keep them somewhere — if you’ve got 100 boxes, this could become a problem), but the main thing is that you need other players to play with on a regular basis. If this isn’t a problem for you, great.

Minimal menu-switching

The game doesn’t switch to another screen when you use the map and/or compass. The compass appears in your right hand, and the map appears on your left. Part of the screen ends up getting covered, but the game world doesn’t stop, and the protagonist can keep moving.

You can zoom in on the compass if you need to.

If you zoom in on the map, it will take up the entire screen, but it’s much easier to get around that way. However, the character can’t sprint when you’re zoomed in on the map.

Additional menus don’t appear when you pick up other items either.

You have the option of examining every item you pick up, even if it has absolutely no effect on the storyline.

● Rotating an item allows you to further immerse yourself in the game world (for example, if you pick up a book, you can examine not only the front cover, but also the spine, and read the notes on the back).

● Zooming in on an item allows you to read documents without opening a special menu.

Which objective is being met: immersion, since the player isn’t distracted by extra menus and doesn’t leave the game world.

Suggested improvements:

You can read the documents you find either as an image or as text by opening a separate menu. If you open the menu, the game is paused (this is clear because, for example, a dialog with Delilah will get cut off mid-word and continue when you’re done reading the document). Since the documents are fairly short, this menu could be gotten rid of. Instead, the documents could be reproduced as images, and the player could zoom in on them like the map. However, this kind of dual text is probably in place to make translation and localization easier.

1. Backpack with equipment

There is always a backpack full of equipment such as a rope and an axe next to the exit. Every time the player clicks on the tower door in order to leave it, the main character picks up the backpack before going outside.

Which objective is being met: this solution increases the player’s belief in what is happening in the game. The usual question of “so my character sleeps in his armor?” doesn’t arise here.

Enhancement of the solution: large items are only pulled out of the backpack when they are needed. For example, you can’t just pull the rope out and unwind it — you can only do it when climbing down a rock face. You can’t just wave the axe around either.

2. Character movement

In general, character movement is much more realistic than in an FPS or action-RPG. This fits well into the game world (after all, you’re playing a heavyset man in his forties with a full backpack on his back), but it could be painful for fans of these genres because of the character’s difficulty overcoming obstacles that the player could just hop over in real life.

Inaccessible areas:

Hills and underbrush. These are used to stop the player from going to places they aren’t supposed to go yet for storyline reasons. Once the character gets the rope and axe, these areas become passable.

Impassable obstacles. The character can’t enter the lake — not even up to his knees — but he can pass over small holes and clamber up gentle slopes.

Safety. The character can’t jump off a cliff or hurt himself in any other way.

Jumping. The character can only jump when necessary, i.e. to overcome obstacles. The player can’t just jump whenever they want to.

Sprinting. The developers made some concessions here. You can sprint at any time (except when using the map). There are also no restrictions on sprinting uphill. Running as fast as a motorcycle obviously isn’t realistic, but we’re all willing to suspend our disbelief here for the sake of saving time and cutting back on frustration.

As you probably noticed, the solutions employed by the developers of Firewatch were all focused on immersion in one way or another. Now the question is, “what do we do with this information?”

I suggest compiling a database of similar solutions. It doesn’t really matter what it looks like. The most important thing is that it will allow you to find several working options for ways to meet a given objective — for example, how to teach the player the controls, how to introduce an antagonist into the game, etc.

It would also be expedient to identify unsuccessful or unsatisfactory ways similar objectives have been met.

When it comes to posting things online, publishing individual breakdowns isn’t the best option for the following reasons.

1. First of all, it’s best to draw conclusions about specific solutions based on multiple breakdowns of games in the same genres rather than just a single game. The kind of breakdown I’m suggesting here is probably just a first step that will allow you to gather examples that you can then analyze and use a basis from which to draw conclusions.

2. Second, if you’re writing for a large audience, this audience will probably include a player who has already spent hundreds or thousands of hours on the game. And if your article is missing anything or contains factual errors, this player will point them out to you — in public.

It’s safer and more useful to only post conclusions with examples from multiple games in the same genre.

Once you’ve broken down a number of games (focus on twenty or so, as long as the games aren’t from very different genres), you’ll have enough material to make a “ten ways to…” video. These videos can be more content-rich and useful than most of the stuff on YouTube right now.

And if you’re disciplined, you won’t have any trouble with content going forward.”

e fica também uma história complementar “How indie developers from Russia make games for Google Play and social networks” e que também é interessante.

+infos(versão traduzida e fonte): LINK

+infos(original): https://habr.com/ru/post/491336/

+infos(história complementar): LINK

Game-designer

“Sou auto-financiado e procuro game designer para pagar por asset.

Projecto:

O jogador embarca em sessões co-op, em multiplayer, para desempenhar missões com game-play stealth, tendo como espionagem o tema do jogo. Todos os jogadores na sessão têm diferentes especialidades e skill-sets que os individualiza e valoriza de diferentes maneiras para completar partes diferentes do objectivo.

Incluí:

– Diálogo e atmosfera rica. (Pensa filmes de Quentin Tarantino)

– Vista primeira pessoa.

– Diferente game-play para especialistas diferentes (jogadores)

Equipa:

– Miguel Nogueira (Criador de projecto, Concept Artist, Generalista 3D)

Game design, concept art e project management. (3 anos de experiência com experiência adicional em VFX, short films e design gráfico desde 2004)

Com destaque em várias comunidades e revistas on-line de artes digitais, como a Kotaku e 80lv.

– João Brito (3D e 2D – Generalista)

Protótipos VR, vencedor da Apple product design awards, dois anos como game developer.

Talent necessário: Game-designer

– Experiência com Unreal Engine toolset é um bonus

– Colaborar na implementação, iteração e ‘ironing out’ de mecânicas de game-play a ser discutidas.

– 3D blockouts (rough)

– Proof of concept, para cada elemento concebido.

– Pontos bónus se fluente em programação.

Por favor mandem experiência e outros materiais que achem relevante para o endereço: miguel.n.design @ gmail.com”

Part-time game development and life balance por Ben Thumbs

Dei de caras na rede social facebook com um post onde estava referido este blog/pagina pessoal de uma Game Designer de nome Ben Thumbs. Ele descreve como é possivel ter três filhos, trabalhar, tirar um mestrado e ao mesmo tempo ser um game designer :)

Apresenta inclusive sugestão de calendário para organização do dia-a-dia :)

Uma dessas sugestões é:

Part-time game developer Mon – Fri example schedules

Early work commitments

4:00am – 6:00am Game development

6:00am – 7:00am Morning routine

7:00am – 5:00pm Work (& commutes)

5:00pm – 9:00pm Free time

9:00pm – 4:00am Sleep

Regular work commitments

5:00am – 7:00am Game development

7:00am – 8:00am Morning routine

8:00am – 6:00pm Work (& commutes)

6:00pm – 10:00pm Free time

10:00pm – 5:00am Sleep

+infos(oficial): LINK

Texto: ODE AO BOM GAME DESIGNER por Isaque Sanches

Este texto relata o que é ser um bom game designer por Isaque Sanches:

— Há bons game designers e maus game designers.

— Ser um bom game designer não se aprende nem se adquire. Há quem nasça um bom game designer e quem não. Um bom game designer nasce ensinado, é um génio, e sabe fazer jogos geniais desde sempre.

— Um bom game designer não precisa de saber nada para além de game design. Algumas soft skills ajudam, mas só pouco.

— Um bom game designer, portanto, para além de não saber programar, não sabe também: ilustrar, animar, modelar, criar som, prototipar nem que seja em papel, fazer estimativas, multiplicar, somar, ou falar com outros seres humanos.

— Se um game designer for bom, o jogo “foi criado” por ele (embora na prática tenha sido desenvolvido por uma equipa). Há de sempre referir-se ao produto final como “o meu jogo”.

— Um bom game designer é manipulador. Tem que ser. Isto porque o seu papel é ser “a pessoa que dá ideias”. Se mais gente der ideias, então ele não serve para nada, logo ninguém pode dar input, fora ou dentro da equipa. Mas se ninguém dá input, começam a surgir frustrações, logo alguma manipulação é necessária para que toda a gente fique feliz, com a impressão falsa que a sua opinião interessa.

— Uma crítica para um bom game designer é uma afronta. Sobretudo se for por parte de um utilizador (jogador). Os jogadores não sabem se o jogo é bom ou não, e é preciso explicar-lhes porque é que tudo faz sentido. Sempre que alguém dá feedback, tem que surgir uma justificação.

— Numa equipa, só há um game designer. Isto porque um game designer também é o RP da equipa. E se uma equipa tem mais do que uma cara, então o público fica confuso. O papel do game designer, para além de explicar a toda a gente que o jogo é da sua autoria, como explicado na alínea acima, é apertar a mão a toda a gente, criar contactos, procurar investimento: é “vender o jogo”, de grosso modo.

— Embora um bom game designer não saiba programar, tem que saber dar input aos programadores. Para isso, tem que aprender alguns termos-chave sem, no entanto, entender o significado destes, ou o contexto em que são usados. Apenas para dar alguns exemplos: buffer, pacotes de informação, responsive, algoritmo, procedural, hashset, shader, “cliente-servidor“, input, collider, runtime.

— Embora um bom game designer não saiba fazer nada na prática, sabe um bocado de tudo no papel, seja qual for o tema, desde cinema, a análises de mercado, a História, Química, Filosofia, e até pesca: sabe tudo, porque tem que saber, porque faz jogos.

— Para um bom game designer “não, porque vi num episódio do Extra Credits que…” é a melhor forma de começar um contra-argumento.

— Um bom game designer não faz level design, não faz diagramas, esquema de mecânicas, não se preocupa com UI, nem se deve interessar em garantir que toda a gente na equipa sabe que jogo está a desenvolver. Um bom game designer vai corrigindo o que está mal. Por exemplo, vê o trabalho de outra pessoa, diz-lhe “isto não pode ser assim”, “manda”-o fazer outra coisa, sem no entanto explicar-lhe bem o quê ao concreto. Se decidir fazer trabalho produtivo, como por exemplo level design, terá que se feito antes da última milestone no calendário de produção, mas sempre depois da penúltima.

— Falando em milestones: um bom game designer sabe que são irrelevantes. São, porque um bom game designer é um deus. Quem decide quando o jogo está pronto é ele, não é o produtor, não é quem investe, não é quem produz conteúdo. Ele é que sabe das datas, por uma razão muito simples que muita gente não compreende: se na última semana entende que um projecto de meses ou anos é para ser todo mudado de uma ponta a outra, é isso mesmo que tem que acontecer.

— Um bom game designer não está sentado, como a ralé que é o resto da equipa. Está de pé, atrás de um programador ou um artista, a olhar para o que está a fazer, de pernas abertas, numa postura militar. Se o game designer for um homem tanto melhor, porque de pernas abertas exibe a sua virilidade e portanto autoridade melhor. Para não parecer um inútil prepotente, o game designer vai ou fazendo perguntas ou dando ordens a quem está à sua frente. As duas frases preferidas de um game designer são “um bocado mais para a esquerda” e “afinal, um bocado mais para a direita”.

— Um bom game designer conhece, usa e abusa da regra do 83%. Que diz, resumidamente que: um número inventado é mais credível quanto mais aleatório for. Por exemplo, diz-se antes sempre 81, 82, 83 ou 84, quando se inventa, nunca 80 ou 85. Concretamente: “fiz um estudo de mercado e 83% do nosso público-alvo…”.

— Para além dessa regra, sabe também que para conquistar é preciso dividir. Para ele, além de o jogo ser “o meu jogo” a equipa é “a minha equipa”. Para a equipa estar nas mãos do game designer, no entanto, este tem que garantir que o diálogo entre membros é mínimo, e passa quase sempre por ele, estilo pombo-correio. Sem esta ferramenta preciosa, o game designer não pode impedir ninguém contribuir criativamente para o jogo.

— E ainda sobre essa regra, há a variante fundamental que é o “diz que disse”. Resumidamente, de novo: o game designer tem uma ideia, fala com o José, pergunta-lhe o que acha, o José diz que sim, e diz à Mariana que o José teve uma ideia incrível, com a qual concorda. Pergunta à Mariana por outra ideia, ela diz “porque não”, e diz ao José que a Mariana teve uma ideia incrível, com a qual concorda. Por sua vez, fala então com o João e o António, que são doutro departamento, e diz-lhes que tanto ele, como o José, como a Mariana, os três, tiveram estas duas ideias, que são na verdade dele.

”

+infos(artigo): http://rubberchickengames.com/2016/05/16/ode-ao-bom-game-designer/