Category: videojogos

IndieCade Europe

IndieCade Europe um canal com os vídeos de um festival/conferência que decorre na Europa.

+infos(IndieCade Europe): LINK

The most influential games of the decade

The most influential games of the decade, por Gene Park , Elise Favis e Mikhail Klimentov

“From the introduction of groundbreaking in-game elements to refining how games make money, these are the titles that made the biggest impact on both players and the industry since 2010.

Gaming is now humanity’s favorite form of entertainment, and the medium’s legacy was cemented this past decade. While the early 2000s saw video games honing their ability to tell stories and build worlds in 3-D, this last decade built off those nuts and bolts of game making and propelled the medium toward bigger ambitions like open-world design, virtual and augmented reality and an influx of new genres such as battle-royale multiplayer.

Video games have experienced a rapidly changing landscape in technology, business models (i.e. microtransactions and the sale of seasonal battle passes), and its market which now includes more female gamers and an older average audience. We’ve seen an increase in diversity in games themselves, too, from the varied races and backgrounds for characters in Overwatch to blockbusters like Horizon: Zero Dawn, which features a headstrong female lead.

This past decade achieved several milestones with its wide array of games. Some, like Red Dead Redemption 2 and Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, are titles that we believe will have a lasting impact on the gaming world for years to come. While these were taken into consideration for this article, we haven’t seen their influence fully resonate just yet, as open-world games take years to polish before they’re shipped and the next generation is still on its way.

So, which games have made the biggest mark on the industry from 2010 through 2019? After much deliberation, here is a list of titles we believe aren’t just quality games, but ones that have shaped the medium and continue to do so in extraordinary ways.

2010 Amnesia: The Dark Descent

Video games are often known for being power fantasies. Even the game that popularized survivor horror, Resident Evil, gave you a rocket launcher and an exploding mansion as its coda. Indie studio Frictional Games dared to make you powerless, with just a lantern in hand to light the way.

It gave you no methods of attack. Hiding in the dark would make you lose your sanity. And don’t even think about glancing at the creatures that stalk you. Amnesia was an unrelenting assault of nightmares. You stand in a flooded basement and see ripples in the water, realizing you’re stuck in there with an invisible horror. All this was a breath of fresh air for a genre whose default dynamic was to slash/shoot/explode your way through terror.

Early this century, publishers were wary of funding survival horror games, and the best franchises were either abandoning the genre (like Resident Evil) or were left abandoned on the roadside (like Silent Hill). Amnesia inspired the phenomenon of horror with a first-person camera perspective, including Alien: Isolation, Outlast and the ill-fated P.T., the “playable teaser” for the infamously canceled Silent Hills directed by Hideo Kojima and Guillermo del Toro.

We are living in Hideo Kojima’s dystopian nightmare. Can he save us?

Amnesia also helped launch the careers of the Internet’s most influential personalities today, most notably PewDiePie. With 102 million subscribers, Felix Kjellberg initially gained viral attention by freaking out over the game, especially the water scene described above. These videos also boosted interest in the game, and publishers noticed. And gamers realized that playing and reacting to horror games was a great way to get views on YouTube. A new celebrity class was born, and the Internet hasn’t been the same since.

2010 Minecraft

What genre is Minecraft? If you call it a survival game, you neglect the sizable portion of its player base which spends its time futzing about in the creative mode, or building elaborate trick doors with redstone. The compromise pick would be to call it a sandbox, but that just takes us back to square one. A sandbox is a blank canvas.

Minecraft represents, in the history of gaming, the ultimate blank canvas. It is The Everything Game by merit of the perfect simplicity of its base formula: building with blocks.

We shouldn’t make the mistake of thinking that The Everything Game just appeared, one day, fully formed. One of Minecraft’s most enduring legacies is the early access model. In the immediate wake of Minecraft’s success, gamers enjoyed an early access boomlet, where players got unprecedented say over future development. It’s not hard to draw the line from indie games in early access to the AAA rebranding of the term “games as a service,” discussed a little later in this article with a look at Destiny, this trend’s most apparent beneficiary.

Few games better encapsulate the 2010s than the ever-popular Minecraft. Analogues and echoes of the decade’s most pressing questions can be found somewhere in its story. The game provided an ideal medium for content creators, who would toil and shape and star in productions that elevated them to stardom and turned YouTube into a juggernaut. Minecraft Let’s Plays picked up the torch after Halo 3 machinima died down, arguably spawning streaming culture. Before Fortnite finally pushed its top creators into the pantheon of celebrity, Minecraft laid the foundation.

We see too the darker trends around social media and celebrity. Minecraft’s most famous creator, Markus Persson, better known as Notch, became the prototypical too-rich, too-disconnected-and-too-online guy, emblematic of a decade dominated by Kanye West and Elon Musk.

Other games will come for Minecraft’s crown. Fortnite has made its bid — but absent a base mode with Minecraft’s flexibility, it has leaned wholly into entertainment and brand collaborations. Minecraft is singular. In the context of the 2010′s, it was a forerunner, the canvas on which, in retrospect, some of the biggest challenges and changes of the decade see their clearest expression.

2011 Dark Souls

Eventually, every video game is compared to Dark Souls. Comparing anything to Dark Souls was a pervasive meme, but in every meme lies some truth. Yes, Dark Souls provided the template for the “Souls-like” genre, games that harshly punish you and set you back for failure. But ideas about player progress, online interactions and environmental storytelling eventually made its way to the rest of the industry.

With no direct contact with each other, players could leave messages, warnings and other thoughts to lift others going through the same, harrowing experience, planting the seed for Hideo Kojima’s grand vision for player interaction in this year’s Death Stranding. Star Wars Jedi: Fallen Order, the best Star Wars game in the last decade, wasn’t shy about its Souls inspiration. And with its exhausting difficulty, From Software challenged and asked us to redefine the very concepts of “fun” and “reward.” It forced us to earn every inch of progress by learning from our mistakes.

Star Wars Jedi: Fallen Order is a good game. So why am I so unhappy playing it?

The game’s story seemed impenetrable at first, but years of analysis has revealed a game layered in mythology and meaning. Every item and enemy is placed with intent. Every room and staircase has purpose. And From Software left out just enough details to spur our imagination, inspiring hundreds of Internet bards to tell tales of their own adventures and the meaning they derived from the game. For some, it was an allegory about the will to survive during depression. For others, it was a nihilistic nightmare railing against the aging belief systems of humanity.

But ask anyone who beat it, and they likely won’t talk about the graphics or the sound or the controls. Dark Souls is the decade’s greatest reminder that video games are more than just stories being told: they are personal, lived experiences.

2011 Skyrim

The fifth Elder Scrolls game from Bethesda Studios became the benchmark for role-playing adventures games in the last decade. While it was really just an evolution of the previous four games, fantasy games went mainstream in a way they never had before Skyrim. Skyrim is, for many, the American role playing game’s Final Fantasy 7. And it was the mother of a thousand memes.

Todd Howard, creative director of Skyrim, said the team hoped Skyrim would enter the pantheon of timeless fantasy worlds.

“The game reflects back on the player as much as possible, ‘who would you be, what would you do in that world?’” Howard said to The Post. “That’s the thing games do better than other entertainment.”

And the game was everywhere, with Howard appearing at news conferences for every known tech company to announce a new version of Skyrim.

But Skyrim caused an explosion in the community modding scene. As Bethesda finally moved on to other games, Skyrim’s players kept the game alive by turning dragons into Thomas the Tank Engine or Macho Man Randy Savage. No other offline game was so online.

If Skyrim seems like the game that just won’t die, it’s because its players refuse to let it die.

“It’s incredible to see so many [people] still playing, even after eight years,” Howard said. “We still marvel at what people are able to do with the game. Maybe that’s why it’s endured for so long.”

2012 Candy Crush Saga

Candy Crush Saga’s humble beginning as a Facebook game makes sense, considering no other title on this list has been as disruptive to the business of selling video games. Candy Crush Saga popularized the “freemium” model within the mobile gaming market: Give the core gameplay away free, but charge for peripheral virtual items that either enhance, quicken or beautify the player’s experience. It married online shopping and gaming to the point where the two were indistinguishable. Mobile gaming eventually created “pay to win” games, referring to video games insidiously designed to slow your progression, encouraging you to pay to win. It is one of the industry’s most despised — and most profitable — practices.

Although a single-digit percentage of players were making these purchases, half a billion people had the game just one year after it released. By 2017, it was downloaded by a third of the human race, at 2.7 billion. Thanks to this small percentage of billions, developer King raked in millions a month.

Activision Blizzard’s purchase of Candy Crush Saga’s Swedish developer in 2015, for $5.9 billion, immediately made it the biggest game publisher in the world. And soon the wildly successful freemium model started to creep into the PC and console space, shaping some of the other games on this list.

It helps that the game is colorful, fun and constantly engaging. Dark Souls and Candy Crush represent the two extreme ends of the gamer populace: casual and hardcore gamers. And regardless of whether they’re aware of it, Candy Crush Saga turned millions of unsuspecting people into gamers.

2012 The Walking Dead: Season One

Reviving adventure games is no small feat, but Telltale’s The Walking Dead was one of the major players that helped reinvigorate the genre. The game told the story of young Clementine and her friendship with Lee, a man whose story began in handcuffs until a zombie apocalypse broke out. The two venture out on a heart-wrenching journey together as they attempt to survive a crippling world’s harsh realities.

Before its release, “adventure games are dead” was a common sentiment in the games industry. The genre had its golden era in the 1980s and early ‘90s, but it then quickly dwindled in popularity. Sales of subsequent adventure games often fell flat, including LucasArts’s Grim Fandango, despite its cult following. Telltale’s The Walking Dead, against all odds, changed everything: It spurred similar games like Life is Strange, Firewatch and Oxenfree — some of which were made by former Telltale developers themselves.

Dontnod Entertainment, the creators of Life is Strange, believes that without The Walking Dead its own choice-driven adventure game may have never existed.

“When we worked on the first Life is Strange, games like The Walking Dead and Quantic Dream’s Heavy Rain were influences for us,” co-director Raoul Barbet said in a phone interview with The Washington Post. “It especially showed us that there was a will from the player to have some games based on choice and storytelling. So I definitely think that without those games, we might not have ended up creating Life is Strange.”

The Walking Dead was a big hit financially, too, popularizing the release of updates in episodic form for far less money than the typical price tag of $60 for a full game. Within its first 20 days of release, the first episode (five were released in total) sold one million copies. In early 2013, Telltale had earned approximately $40 million in revenue solely from the debut season.

The Walking Dead showed the games industry that there was a hunger for deeper, stronger, and choice-driven storytelling, and it became one of Telltale’s crown jewels — one it tried to replicate time and time again, until the studio closed down in late 2018. The studio isn’t completely gone, however: A new iteration of Telltale is now working with independent studio AdHoc (made up of ex-Telltale designers) to produce the once-cancelled The Wolf Among Us 2.

2014 Destiny

Recent years have introduced the concept of video games as a service or “live service games.” Destiny crystallized that model, despite its early missteps.

When released, reviews of Destiny were harsh. Activities were boring, the loot was inadequate, the story was nonsense. Destiny’s disastrous launch was an omen that these persistent “games as a service” titles will be really hard to not only make, but maintain. Destiny’s early missteps were repeated not only by its competitors, but even by Bungie itself for Destiny 2.

But Bungie would right the ship, which also demonstrated the beauty of the “games as a service” model. The developers responded to community feedback and ultimately chiseled the game into something closer to its original vision of a “shared world shooter.” Seasons changed its evolving and expanding story, and Bungie introduced challenges to give anyone a reason to log in every day.

“I vividly remember first hearing about Destiny as a Bungie employee,” said Luke Smith, game director for Destiny 2. “[Co-founder] Jason Jones said the next game was going to be a hobby, like golf. The hobby construction of a game immediately resonated with me. Community and a return to aspects like what we saw in World of Warcraft in a shooter? That was all I needed to hear to get in.”

Destiny 2 is now free, and remains one of the healthiest, vibrant communities, as it won The Game Award in 2019 for best community support. The story of gaming’s decade is incomplete without Destiny turning its high-profile failure into an ever-moving goal post for anyone else who would dare to mimic Bungie’s aspirations.

2015 The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt

The world of The Witcher 3 is so large it can be almost daunting, but this magnitude set a new standard for open-world design. Its sprawling narrative seamlessly fits inside the world, both through emergent storytelling and scripted moments, as you travel from one village to the next. During development, creator CD Projekt Red looked to Skyrim, which released just a few years beforehand, as inspiration. But they didn’t want to just copy what Skyrim got right.

“We drew inspiration from a whole range of titles, and Skyrim was definitely among them; it was the benchmark for open-world games back then,” The Witcher 3 writer Jakub Szamałek told The Post. “At the same time, while there’s a lot to learn from the folks from Bethesda, we knew we didn’t want to simply copy their game. Most importantly, we put a much greater emphasis on the narrative aspect of the game.”

The Witcher 3 tells the story of Geralt, a powerful monster-killing sorcerer who makes his way through a medieval-inspired land to find a young woman named Ciri. Depending on your choices — and some can be heart wrenching — the world adapts around you. It also features side quests that are as meaningful as the main line quest, bringing depth to every corner of the game’s immense world. Most of all, The Witcher 3 set the high bar for storytelling in subsequent open-world games like last year’s Red Dead Redemption 2, dispelling the notion that open worlds and quality storytelling couldn’t coexist.

“I guess before The Witcher 3, it was commonly assumed that ambitious narratives and open world games don’t mix well: you can have one, but not the other,” Szamałek said. “I think we demonstrated that while it is difficult, as well as time- and resource-consuming, it’s within the realm of possibility. Over the past few years we’ve seen more games that combine sprawling open worlds with well-crafted stories, and if in some small part it is due to the success of The Witcher 3, well, I couldn’t be more pleased, both as a game developer and a gamer.”

2016 Pokémon Go

When discussing the influence of Pokémon Go, it’s best to address the question of augmented reality (AR) upfront, so here goes: Pokémon Go is the clearest evidence of AR’s irrelevance.

When the game came out, the hype was tremendous. With its massive success (over 540 million downloads to date), Pokémon Go was the game that launched a thousand decks, prompting questions from every tech, media and software company as to how AR could factor into its work. And then the hype died down. It is funny, in retrospect, that AR’s killer app is such a capitulation. The game allows you to turn off its AR capabilities, and frankly, is all the better for it. Nobody wants to be the overeager jerk on the subway platform, sweatily pivoting back and forth trying to find the Pidove hiding among the commuters.

Worse yet, Pokémon Go is an obvious and not particularly artful exploitation of a beloved childhood property. We’ll see more and more of this over time (Exhibit A: Niantic’s Harry Potter game). And so its true influence isn’t really anything in the game — neither technology nor license. It’s in what the game demands of you: Pokémon Go is a game that’s meant to be played in between doing other things. You’re at a Starbucks, so might as well check into the Poke Stop. Think you’ve walked enough to hatch your eggs? Better check back in. It’s gaming in the micro-moments of your day.

But now, the twist: So many people, and people you would not expect, still keep up with Pokémon Go. Plenty of folks have found routine and comfort in the game. There’s something concerning, but also weirdly resilient, about finding nourishment in gruel so thin.

Pokémon is everywhere now. Long live Pokémon.

Pokémon Go is the “I’m always listening to podcasts or music because I don’t want to be alone with my own thoughts” of games. It’s unlikely that we’ll see many one-to-one Pokémon Go clones in the future. Instead, we’ll be besieged by games that try to cram themselves into the quiet moments and spaces of everyday life.

2017 Fortnite

No, Fortnite is not on here because it popularized the battle royale genre. Fortnite’s best-known mode is itself a result of the popularization of the genre, thanks to PlayerUnknown’s Battleground. But once Epic Games successfully aped the formula, Fortnite found new ways to keep players engaged. The game was free, but the battle pass system kept players subscribing every few months to log on and garner new rewards. Thanks to several controversies that coincided with the rollout of the game’s battle pass, the loot box practice of offering surprise rewards for real money became a pariah of the industry.

Fortnite offered 100 tiers of rewards for only $10 every few months in a “season,” and players got to see everything they would win along the way. The transparency and low commitment cost kept players coming back and — combined with direct payments for skins and other cosmetics offered outside of the battle pass — suddenly the industry found a winning formula. Soon, everyone from Call of Duty to Halo to Overwatch had a similar battle pass system.

Then there was the spectacle of the game. Every season would end with a global event witnessed by millions over streaming platforms like Twitch, elevating personalities like Tyler “Ninja” Blevins, Turner “Tfue” Tenney, Soleil “Ewok” Wheeler and many others alongside the game. Both the streamers and Fortnite smashed through screens and into the mainstream — and ultimately helped people like Blevins and Wheeler ink exclusive streaming contracts worth millions.

Over the last three years, Fortnite was everywhere. At one point, it boasted more than 200 million players a month, and became the biggest pop phenomenon of 2018. World Cup goals were celebrated with Fortnite dances. Former first lady Michelle Obama even did a dance. Major sports leagues worried about players not sleeping or training because of the game. It held an in-game concert, and then, this December, an in-game screening of a scene for the new Star Wars movie — the latest pop-culture crossover event for a game that’s also featured Netflix series “Stranger Things” and Marvel’s Avengers movies.

Epic Games declined to discuss Fortnite’s legacy, citing — as its team often does — that it prefers to let the game speak for itself. At the end of the decade, Fortnite is still speaking in volumes.

”

+infos(origem do texto): LINK

+infos(washington post): https://www.washingtonpost.com/video-games/

Estudos sobre gamedesign e assuntos relacionados!

A Carnegie Mellon University, mais concretamente o Carnegie Mellon University – Entertainment Technology Center, nos estados unidos tem uma série de documentos LIVRES acerca do design de videojogos. Nesta altura os títulos que encontrei foram:

Beyond Fun de Drew Davidson

Analog Game Studies, volume one, de Emma Leigh Waldron, Evan Torner, Aaron Trammell

Analog Game Studies, volume three, de Emma Leigh Waldron, Aaron Trammell, Evan Torner

Analog Game Studies, volume two, de Aaron Trammell, Emma Leigh Waldron, Evan Torner

Game Design Research de Petri Lankoski, Jussi Holopainen

Game Design Snacks de José P. Zagal

Game Jam Guide de Sara Cornish, Matthew Farber, Alex Fleming, Kevin Miklasz

Game Mods de Erik Champion

Game Research Methods de Petri Lankoski, Staffan Björk

Learning, Education and Games (Vol. 1) de Karen Schrier

Learning, Education and Games (Vol. 2) de Karen Schrier

Ludoliteracy de José P. Zagal

Missions for Thoughtful Gamers de Andrew Cutting

Mobile Media Learning de Seann Dikkers, John Martin, Bob Coulter

Mobile Media Learning de Christopher Holden, Seann Dikkers, John Martin, Breanne Litts

Possible Worlds in Video Games de Antonio José Planells de la Maza

Real Time Research de Seann Dikkers, Eric Zimmerman, Kurt Squire, Constance Steinkuehler

Tabletop de Greg Costikyan, Drew Davidson

The Game Beat de Kyle Orland

Transmedia Storytelling de Max Giovagnoli

Well Played 1.0 de Drew Davidson

Well Played 2.0 de Drew Davidson

Well Played 3.0 de Drew Davidson

+infos(oficial): http://press.etc.cmu.edu/

Handmade pixels: independent video games and the quest for authenticity

:) hoje é dia para divulgar por aqui livros, mais um: “Handmade pixels: independent video games and the quest for authenticity” de Jesper Juul

Acerca do livro:

“An investigation of independent video games—creative, personal, strange, and experimental—and their claims to handcrafted authenticity in a purely digital medium.

Video games are often dismissed as mere entertainment products created by faceless corporations. The last twenty years, however, have seen the rise of independent, or “indie,” video games: a wave of small, cheaply developed, experimental, and personal video games that react against mainstream video game development and culture. In Handmade Pixels, Jesper Juul examine the paradoxical claims of developers, players, and festivals that portray independent games as unique and hand-crafted objects in a globally distributed digital medium.

Juul explains that independent video games are presented not as mass market products, but as cultural works created by people, and are promoted as authentic alternatives to mainstream games. Writing as a game player, scholar, developer, and educator, Juul tells the story of how independent games—creative, personal, strange, and experimental—became a historical movement that borrowed the term “independent” from film and music while finding its own kind of independence.

Juul describes how the visual style of independent games signals their authenticity—often by referring to older video games or analog visual styles. He shows how developers use strategies for creating games with financial, aesthetic, and cultural independence; discusses the aesthetic innovations of “walking simulator” games; and explains the controversies over what is and what isn’t a game. Juul offers examples from independent games ranging from Dys4ia to Firewatch; the text is richly illustrated with many color images.”

Os conteúdos são:

Introduction

High-Tech Low-Tech Authenticity: The Creation of Independent Style at the Independent Games Festival

A selective History of Independen Games

How to Make and Independent Games

The Aesthetics of the Aesthetics of the Aesthetics of Video Games

Whoe Cares If It’s a Game?

Conclusions: Independent Evermore

+infos(oficial): LINK

Time and Space in Video Games: A Cognitive-Formalist Approach

Outro livro que gostava de ter acesso: Time and Space in Video Games: A Cognitive-Formalist Approach (Studies of Digital Media Culture, Bd. 9) de Federico Alvarez Igarzábal

“Video games are temporal artifacts: They change with time as players interact with them in accordance with rules. In this study, Federico Alvarez Igarzábal investigates the formal aspects of video games that determine how these changes are produced and sequenced. Theories of time perception drawn from the cognitive sciences lay the groundwork for an in-depth analysis of these features, making for a comprehensive account of time in this novel medium. The first book-length study exclusively dedicated to the topic, it is an indispensable resource for game scholars and game developers alike, while its reader-friendly style makes it readily accessible to the interested layperson.”

os conteúdos são:

Brain time in virtual space

“the state machine and the present moment”

“structuring gametime”

“cause, effect, and player-centric time

Interation in virtual space

“predictive thinking in virtual worlds”

“the goundhog day effect”

“the hybrid narrator”

Through the temporal landscape

“the speed of time”

“marshmallows and bullets”

“Chekhov’s BFG”

Conclusion

+infos(oficial): LINK

+infos(google books): LINK

The Pyramid of Game Design

Gostava de ter acesso a este livro “The Pyramid of Game Design” de Nicholas Lovell:

“Game design is changing. The emergence of service games on PC, mobile and console has created new expectations amongst consumers and requires new techniques from game makers.

In The Pyramid of Game Design, Nicholas Lovell identifies and explains the frameworks and techniques you need to deliver fun, profitable games. Using examples of games ranging from modern free-to-play titles to the earliest arcade games, via PC strategy and traditional boxed titles, Lovell shows how game development has evolved, and provides game makers with the tools to evolve with it.

Harness the Base, Retention and Superfan Layers to create a powerful Core Loop.

Design the player Session to keep players playing while being respectful of their time.

Accept that there are few fixed rules: just trade-offs with consequences.

Adopt Agile and Lean techniques to “learn what you need you learn” quickly

Use analytics, paired with design skills and player feedback, to improve the fun, engagement and profitability of your games.

Adapt your marketing techniques to the reality of the service game era

Consider the ethics of game design in a rapidly changing world.

Lovell shows how service games require all the skills of product game development, and more. He provides a toolset for game makers of all varieties to create fun, profitable games. Filled with practical advice, memorable anecdotes and a wealth of game knowledge, the Pyramid of Game Design is a must-read for all game developers.

”

+infos(editora): LINK

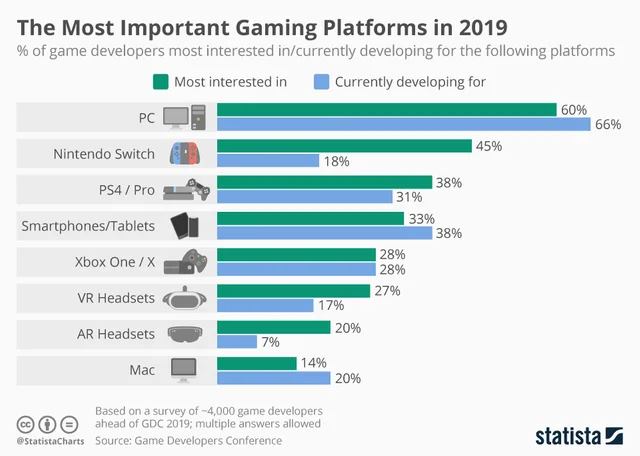

Ainda não terminou o ano mas..

A malta da STATISTA libertou mais umas informações acerca de um estudo que fizeram aos dev de videojogos, e não é que o PC aparece ainda como primeira opção e local de desenvolvimento atual :)

The Unity Game Engine and the Circuits of Cultural Software e Graduate Skills and Game-Based Learning

Gostava de ter acesso a este livro “The Unity Game Engine and the Circuits of Cultural Software” de Nicoll, Benjamin e Keogh, Brendan

“Videogames were once made with a vast range of tools and technologies, but in recent years a small number of commercially available ‘game engines’ have reached an unprecedented level of dominance in the global videogame industry. In particular, the Unity game engine has penetrated all scales of videogame development, from the large studio to the hobbyist bedroom, such that over half of all new videogames are reportedly being made with Unity. This book provides an urgently needed critical analysis of Unity as ‘cultural software’ that facilitates particular production workflows, design methodologies, and software literacies. Building on long-standing methods in media and cultural studies, and drawing on interviews with a range of videogame developers, Benjamin Nicoll and Brendan Keogh argue that Unity deploys a discourse of democratization to draw users into its ‘circuits of cultural software’. For scholars of media production, software culture, and platform studies, this book provides a framework and language to better articulate the increasingly dominant role of software tools in cultural production. For videogame developers, educators, and students, it provides critical and historical grounding for a tool that is widely used yet rarely analysed from a cultural angle.”

+infos(oficial): LINK

E a este livro “Graduate Skills and Game-Based Learning – Using Video Games for Employability in Higher Education” por Matthew Barr.

“Graduate Skills and Game-Based Learning offers us a new tool for the heart and soul of graduate education, a tool for experimentation, risk-taking, creativity, and using failure as a form of learning. These are just the bits where we need the most help.”

+infos(oficial): LINK

Cecilia D’Anastasio, uma repórter no mundo dos videojogos

Vi esta referência a este video “The Dark Side of the Video Game Industry | Patriot Act with Hasan Minhaj | Netflix” de um “comediante/show/serious talking” de alguém que fala um pouco da industria no mercado dos videojogos, recomendo a audição do mesmo, e a reflexão sobre:

+infos(GMU oficial): https://www.gameworkersunite.org/

E recomendo a leitura (a quem interessar) desta repórter/escritora de nome Cecilia D’Anastasio. Ela em feito um conjunto de textos que aborda por um lado as mulheres no mundo de desenvolvimento de videojogos e também tem outras abordagens (textos) mais de reflexão sobre o que se tem passado nesta industria, que como as outras, tem os seus grandes problemas.

+infos(pagina oficial): http://www.cecianasta.com/articles

+infos(aceerca da Cecilia D’Anastasio): LINK

Uma campanha que vem do outro lado do mundo!

Está a decorrer uma campanha numa plataforma de crowdfunding com o nome “Bem Vindo Ao Game Design – Livro e Cursos Online” por João Victor Santos Pinho Teixeira. O objectivo é o de apoiar a publicação de um livro relacionado com o desenvolvimento de videojogos.

+infos(oficial): LINK

Um texto interessante acerca do uso de videojogos

Encontrei este post acerca do uso de videojogos e as possíveis mudanças que eles podem trazer. Com o título “Can gaming inspire social change?” por Anjuli Borgonha.

+infos(oficial): LINK

Livro: A History of Videogames

Mais um livro que gostava de ter acesso:

A History of Videogames, de Iain Simons, James Newman, e Ian Livingstone

+infos(comprar): LINK

A história acerca da pirataria dos videojogos no Brasil

Uma história acerca da pirataria dos videojogos no Brasil. São três episódios:

Episódio 1 – Arcades Improvisados

“Com as máquinas de pinball da Taito, a indústria dos games no Brasil teve seu começo nas lojas sujas do centro de São Paulo e nas fábricas poluídas do Amazonas. Isso marcou o início de uma cultura gamer recheada de adaptações e clones nacionais muitas vezes criados às margens da lei.”

Episódio 2 – Consoles e jogos nacionais

“O Brasil passa a ter não só um mercado estável, mas também os primeiros jogadores. O lance é que grandes empresas, como a Nintendo, não estavam oficialmente no país. Então, alguns empreendedores começaram a criar os primeiros emuladores: produtos nacionais que eram adaptações de games e consoles populares. Como o Master System, da TecToy, e o Phantom System, da Gradiente.”

Episódio 3 – Modificações e o começo do eSports

“Na virada dos anos 2000, com os cartuchos dando lugar aos CDs e DVDs, a cultura de games no Brasil teve uma febre modder. Patchs de jogos mainstream como Winning Eleven (PlayStation 2) e Counter-Strike (PC) eram mais populares que os games originais, fazendo empresas como Microsoft e Sony finalmente chegarem oficialmente ao país. Também foi o começo da cultura de eSports no Brasil.”

+infos(fonte): LINK , pela RedBull

+1a história.. acerca do desenvolvimento de videojogos

Como não existem duas sem três, aqui fica mais uma referência acerca do desenvolvimento de videojogos ao longo dos tempos. A narrativa começa pelo uso de consolas em casa..1940

Since its commercial birth in the 1950s as a technological oddity at a science fair, gaming has blossomed into one of the most profitable entertainment industries in the world.

The mobile technology boom in recent years has revolutionized the industry and opened the doors to a new generation of gamers. Indeed, gaming has become so integrated with modern popular culture that now even grandmas know what Angry Birds is, and more than 42 percent of Americans are gamers and four out of five U.S. households have a console.

The Early Years

The first recognized example of a game machine was unveiled by Dr. Edward Uhler Condon at the New York World’s Fair in 1940. The game, based on the ancient mathematical game of Nim, was played by about 50,000 people during the six months it was on display, with the computer reportedly winning more than 90 percent of the games.

However, the first game system designed for commercial home use did not emerge until nearly three decades later, when Ralph Baer and his team released his prototype, the “Brown Box,” in 1967.

The “Brown Box” was a vacuum tube-circuit that could be connected to a television set and allowed two users to control cubes that chased each other on the screen. The “Brown Box” could be programmed to play a variety of games, including ping pong, checkers and four sports games. Using advanced technology for this time, added accessories included a lightgun for a target shooting game, and a special attachment used for a golf putting game.

According to the National Museum of American History, Baer recalled, “The minute we played ping-pong, we knew we had a product. Before that we weren’t too sure.”

Magnavox-OdysseyThe “Brown Box” was licensed to Magnavox, which released the system as the Magnavox Odyssey in 1972. It preceded Atari by a few months, which is often mistakenly thought of as the first games console.

Between August 1972 and 1975, when the Magnavox was discontinued, around 300,000 consoles were sold. Poor sales were blamed on mismanaged in-store marketing campaigns and the fact that home gaming was a relatively alien concept to the average American at this time.

However mismanaged it might have been, this was the birth of the digital gaming we know today.

Onward To Atari And Arcade Gaming

Sega and Taito were the first companies to pique the public’s interest in arcade gaming when they released the electro-mechanical games Periscope and Crown Special Soccer in 1966 and 1967. In 1972, Atari (founded by Nolan Bushnell, the godfather of gaming) became the first gaming company to really set the benchmark for a large-scale gaming community.

The nature of the games sparked competition among players, who could record their high scores … and were determined to mark their space at the top of the list.

Atari not only developed their games in-house, they also created a whole new industry around the “arcade,” and in 1973, retailing at $1,095, Atari began to sell the first real electronic video game Pong, and arcade machines began emerging in bars, bowling alleys and shopping malls around the world. Tech-heads realized they were onto a big thing; between 1972 and 1985, more than 15 companies began to develop video games for the ever-expanding market.

The Roots Of Multiplayer Gaming As We Know It

During the late 1970s, a number of chain restaurants around the U.S. started to install video games to capitalize on the hot new craze. The nature of the games sparked competition among players, who could record their high scores with their initials and were determined to mark their space at the top of the list. At this point, multiplayer gaming was limited to players competing on the same screen.

The first example of players competing on separate screens came in 1973 with “Empire” — a strategic turn-based game for up to eight players — which was created for the PLATO network system. PLATO (Programmed Logic for Automatic Teaching Operation), was one of the first generalized computer-based teaching systems, originally built by the University of Illinois and later taken over by Control Data (CDC), who built the machines on which the system ran.

According to usage logs from the PLATO system, users spent about 300,000 hours playing Empire between 1978 and 1985. In 1973, Jim Bowery released Spasim for PLATO — a 32-player space shooter — which is regarded as the first example of a 3D multiplayer game. While access to PLATO was limited to large organizations such as universities — and Atari — who could afford the computers and connections necessary to join the network, PLATO represents one of the first steps on the technological road to the Internet, and online multiplayer gaming as we know it today.

At this point, gaming was popular with the younger generations, and was a shared activity in that people competed for high-scores in arcades. However, most people would not have considered four out of every five American households having a games system as a probable reality.

Home Gaming Becomes A Reality

In addition to gaming consoles becoming popular in commercial centers and chain restaurants in the U.S., the early 1970s also saw the advent of personal computers and mass-produced gaming consoles become a reality. Technological advancements, such as Intel’s invention of the world’s first microprocessor, led to the creation of games such as Gunfight in 1975, the first example of a multiplayer human-to-human combat shooter.

While far from Call of Duty, Gunfight was a big deal when it first hit arcades. It came with a new style of gameplay, using one joystick to control movement and another for shooting direction — something that had never been seen before.

In 1977, Atari released the Atari VCS (later known as the Atari 2600), but found sales slow, selling only 250,000 machines in its first year, then 550,000 in 1978 — well below the figures expected. The low sales have been blamed on the fact that Americans were still getting used to the idea of color TVs at home, the consoles were expensive and people were growing tired of Pong, Atari’s most popular game.

When it was released, the Atari VCS was only designed to play 10 simple challenge games, such as Pong, Outlaw and Tank. However, the console included an external ROM slot where game cartridges could be plugged in; the potential was quickly discovered by programmers around the world, who created games far outperforming the console’s original designed.

The integration of the microprocessor also led to the release of Space Invaders for the Atari VCS in 1980, signifying a new era of gaming — and sales: Atari 2600 sales shot up to 2 million units in 1980.

As home and arcade gaming boomed, so too did the development of the gaming community. The late 1970s and early 1980s saw the release of hobbyist magazines such as Creative Computing (1974), Computer and Video Games (1981) and Computer Gaming World (1981). These magazines created a sense of community, and offered a channel by which gamers could engage.

Personal Computers: Designing Games And Opening Up To A Wider Community

The video game boom caused by Space Invaders saw a huge number of new companies and consoles pop up, resulting in a period of market saturation. Too many gaming consoles, and too few interesting, engaging new games to play on them, eventually led to the 1983 North American video games crash, which saw huge losses, and truckloads of unpopular, poor-quality titles buried in the desert just to get rid of them. The gaming industry was in need of a change.

At more or less the same time that consoles started getting bad press, home computers like the Commodore Vic-20, the Commodore 64 and the Apple II started to grow in popularity. These new home computer systems were affordable for the average American, retailing at around $300 in the early 1980s (around $860 in today’s money), and were advertised as the “sensible” option for the whole family.

These home computers had much more powerful processors than the previous generation of consoles; this opened the door to a new level of gaming, with more complex, less linear games. They also offered the technology needed for gamers to create their own games with BASIC code. Even Bill Gates designed a game, called Donkey (a simple game that involved dodging donkeys on a highway while driving a sports car). Interestingly, the game was brought back from the dead as an iOS app back in 2012.

While the game was described at the time as “crude and embarrassing” by rivals at Apple, Gates included the game to inspire users to develop their own games and programs using the integrated BASIC code program.

Magazines like Computer and Video Games and Gaming World provided BASIC source code for games and utility programs, which could be typed into early PCs. Games, programs and readers’ code submissions were accepted and shared.

In addition to providing the means for more people to create their own game using code, early computers also paved the way for multiplayer gaming, a key milestone for the evolution of the gaming community.

Early computers such as the Macintosh, and some consoles such as the Atari ST, allowed users to connect their devices with other players as early as the late 1980s. In 1987, MidiMaze was released on the Atari ST and included a function by which up to 16 consoles could be linked by connecting one computer’s MIDI-OUT port to the next computer’s MIDI-IN port.

While many users reported that more than four players at a time slowed the game dramatically and made it unstable, this was the first step toward the idea of a deathmatch, which exploded in popularity with the release of Doom in 1993 and is one of the most popular types of games today.

The real revolution in gaming came when LAN networks, and later the Internet, opened up multiplayer gaming.

Multiplayer gaming over networks really took off with the release of Pathway to Darkness in 1993, and the “LAN Party” was born. LAN gaming grew more popular with the release of Marathon on the Macintosh in 1994 and especially after first-person multiplayer shooter Quake hit stores in 1996. By this point, the release of Windows 95 and affordable Ethernet cards brought networking to the Windows PC, further expanding the popularity of multiplayer LAN games.

Multiplayer gaming took the gaming community to a new level because it allowed fans to compete and interact from different computers, which improved the social aspect of gaming. This key step set the stage for the large-scale interactive gaming that modern gamers currently enjoy. On April 30, 1993, CERN put the World Wide Web software in the public domain, but it would be years before the Internet was powerful enough to accommodate gaming as we know it today.

The Move To Online Gaming On Consoles

Long before gaming giants Sega and Nintendo moved into the sphere of online gaming, many engineers attempted to utilize the power of telephone lines to transfer information between consoles.

William von Meister unveiled groundbreaking modem-transfer technology for the Atari 2600 at the Consumer Electronics Show (CES) in Las Vegas in 1982. The new device, the CVC GameLine, enabled users to download software and games using their fixed telephone connection and a cartridge that could be plugged in to their Atari console.

The device allowed users to “download” multiple games from programmers around the world, which could be played for free up to eight times; it also allowed users to download free games on their birthdays. Unfortunately, the device failed to gain support from the leading games manufacturers of the time, and was dealt a death-blow by the crash of 1983.

Real advances in “online” gaming wouldn’t take place until the release of 4th generation 16-bit-era consoles in the early 1990s, after the Internet as we know it became part of the public domain in 1993. In 1995 Nintendo released Satellaview, a satellite modem peripheral for Nintendo’s Super Famicom console. The technology allowed users to download games, news and cheats hints directly to their console using satellites. Broadcasts continued until 2000, but the technology never made it out of Japan to the global market.

Between 1993 and 1996, Sega, Nintendo and Atari made a number of attempts to break into “online” gaming by using cable providers, but none of them really took off due to slow Internet capabilities and problems with cable providers. It wasn’t until the release of the Sega Dreamcast, the world’s first Internet-ready console, in 2000, that real advances were made in online gaming as we know it today. The Dreamcast came with an embedded 56 Kbps modem and a copy of the latest PlanetWeb browser, making Internet-based gaming a core part of its setup rather than just a quirky add-on used by a minority of users.

The Dreamcast was a truly revolutionary system, and was the first net-centric device to gain popularity. However, it also was a massive failure, which effectively put an end to Sega’s console legacy. Accessing the Internet was expensive at the turn of the millennium, and Sega ended up footing huge bills as users used its PlanetWeb browser around the world.

Experts related the console’s failure to the Internet-focused technology being ahead of its time, as well as the rapid evolution of PC technology in the early 2000s — which led people to doubt the use of a console designed solely for gaming. Regardless of its failure, Dreamcast paved the way for the next generation of consoles, such as the Xbox. Released in the mid-2000s, the new console manufacturers learned from and improved the net-centric focus of the Dreamcast, making online functionality an integral part of the gaming industry.

The release of Runescape in 2001 was a game changer. MMORPG (massively multiplayer online role-playing games) allows millions of players worldwide to play, interact and compete against fellow fans on the same platform. The games also include chat functions, allowing players to interact and communicate with other players whom they meet in-game. These games may seem outdated now, but they remain extremely popular within the dedicated gaming community.

The Modern Age Of Gaming

Since the early 2000s, Internet capabilities have exploded and computer processor technology has improved at such a fast rate that every new batch of games, graphics and consoles seems to blow the previous generation out of the water. The cost of technology, servers and the Internet has dropped so far that Internet at lightning speeds is now accessible and commonplace, and 3.2 billion people across the globe have access to the Internet. According to the ESA Computer and video games industry report for 2015, at least 1.5 billion people with Internet access play video games.

Online storefronts such as Xbox Live Marketplace and the Wii Shop Channel have totally changed the way people buy games, update software and communicate and interact with other gamers, and networking services like Sony’s PSN have helped online multiplayer gaming reach unbelievable new heights.

Every new batch of games, graphics and consoles seems to blow the previous generation out of the water.

Technology allows millions around the world to enjoy gaming as a shared activity. The recent ESA gaming report showed that 54 percent of frequent gamers feel their hobby helps them connect with friends, and 45 percent use gaming as a way to spend time with their family.

By the time of the Xbox 360 release, online multiplayer gaming was an integral part of the experience (especially “deathmatch” games played against millions of peers around the world for games such as Call of Duty Modern Warfare). Nowadays, many games have an online component that vastly improves the gameplay experience and interactivity, often superseding the importance of the player’s offline game objectives.

“What I’ve been told as a blanket expectation is that 90% of players who start your game will never see the end of it…” says Keith Fuller, a longtime production contractor for Activision.

As online first-person shooter games became more popular, gaming “clans” began to emerge around the world. A clan, guild or faction is an organized group of video gamers that regularly play together in multiplayer games. These games range from groups of a few friends to 4,000-person organizations with a broad range of structures, goals and members. Multiple online platforms exist, where clans are rated against each other and can organize battles and meet-ups online.

The Move Toward Mobile

Since smartphones and app stores hit the market in 2007, gaming has undergone yet another rapid evolution that has changed not only the way people play games, but also brought gaming into the mainstream pop culture in a way never before seen. Rapid developments in mobile technology over the last decade have created an explosion of mobile gaming, which is set to overtake revenue from console-based gaming in 2015.

This huge shift in the gaming industry toward mobile, especially in Southeast Asia, has not only widened gaming demographics, but also pushed gaming to the forefront of media attention. Like the early gaming fans joining niche forums, today’s users have rallied around mobile gaming, and the Internet, magazines and social media are full of commentaries of new games and industry gossip. As always, gamers’ blogs and forums are filled with new game tips, and sites such as Macworld, Ars Technica and TouchArcade push games from lesser-known independent developers, as well as traditional gaming companies.

The gaming industry was previously monopolized by a handful of companies, but in recent years, companies such as Apple and Google have been sneaking their way up the rankings due to their games sales earnings from their app stores. The time-killing nature of mobile gaming is attractive to so many people who basic games such as Angry Birds made Rovio $200 million in 2012 alone, and broke two billion downloads in 2014.

More complex mass multiplayer mobile games such as Clash of Clans are bringing in huge sums each year, connecting millions of players around the world through their mobile device or League of Legends on the PC.

The Future

The move to mobile technology has defined the recent chapter of gaming, but while on-the-move gaming is well-suited to the busy lives of millennials, gaming on mobile devices also has its limitations. Phone screens are small (well, at least until the iPhone 6s came out), and processor speeds and internal memories on the majority of cellphones limit gameplay possibilities. According to a recent VentureBeat article, mobile gaming is already witnessing its first slump. Revenue growth has slowed, and the cost of doing business and distribution costs have risen dramatically over the last few years.

Although mobile gaming has caused the death of hand-held gaming devices, consoles are still booming, and each new generation of console welcomes a new era of technology and capabilities. Two industries that could well play a key role in the future of gaming are virtual reality and artificial intelligence technology.

Virtual reality (VR) company Oculus was acquired by Facebook in 2014, and is set to release its Rift headset in 2016. The headset seems to lean perfectly toward use within the video games industry, and would potentially allow gamers to “live” inside an interactive, immersive 3D world. The opportunities to create fully interactive, dynamic “worlds” for MMORPG, in which players could move around, interact with other players and experience the digital landscapes in a totally new dimension, could be within arms reach.

There have been a lot of advancements over the last few years in the world of language-processing artificial intelligence. In 2014, Google acquired Deep Mind; this year, IBM acquired AlchemyAPI, a leading provider in deep-learning technology; in October 2015, Apple made two AI acquisitions in less than a week. Two of the fields being developed are accuracy for voice recognition technology and open-ended dialogue with computers.

These advances could signify an amazing new chapter for gaming — especially if combined with VR, as they could allow games to interact with characters within games, who would be able to respond to questions and commands, with intelligent and seemingly natural responses. In the world of first-person shooters, sports games and strategy games, players could effectively command the computer to complete in-game tasks, as the computer would be able to understand commands through a headset due to advances in voice recognition accuracy.

If the changes that have occurred over the last century are anything to go by, it appears that gaming in 2025 will be almost unrecognizable to how it is today. Although Angry Birds has been a household name since its release in 2011, it is unlikely to be remembered as fondly as Space Invaders or Pong. Throughout its progression, gaming has seen multiple trends wane and tide, then be totally replaced by another technology. The next chapter for gaming is still unclear, but whatever happens, it is sure to be entertaining.

+infos(fonte da informação): LINK, por Riad Chikhani

Video Game History Foundation

Aqui está mais um daqueles sites interessantes e a ver se tem pernas para andar. O assunto tem, mas vamos ver se tem força para permanecer e crescer :) Espero que sim.

+infos(Video Game History Foundation): https://gamehistory.org/

Mais um achado em português

Encontrei um blog que tem como tradição postar noticias acerca de videojogos do ZX Spectrum, em português! :)

Destaco também o arquivo que eles partilham acerca das noticias de jornais sobre videojogos e estas tecnologias .. e sem deixar de lado o jornal A Capital :) todas as sextas ;)

+infos(blog): https://planetasinclair.blogspot.com/

História dos videojogos :) (mais um livro)

Encontrei mais uma referência a um livro acerca de videojogos para “consolas” de 8 bits, onde se inclui o meu favorito, ZX Spectrum. Ainda não é desta que vou comprar já que o preço ronda perto dos 50 euros :(

+infos(oficial): LINK

Um pouco de história..

Um post interessante acerca da história no desenvolvimento gráfico dos videojogos que foram desenvolvidos no Japão por VGDensetsu.

+infos(post): LINK

Livros interessantes… (e que gostava de ter acesso)

Resonant Games Design Principles for Learning Games that Connect Hearts, Minds, and the Everyday de Eric Klopfer, Jason Haas, Scot Osterweil and Louisa Rosenheck (LINK)

Future Gaming Creative Interventions in Video Game Culture de Paolo Ruffino (LINK)

Connected Gaming What Making Video Games Can Teach Us about Learning and Literacy de Yasmin B. Kafai and Quinn Burke (LINK)

How Games Move Us Emotion de Design de Katherine Isbister (LINK)

e estudos compilados em livros:

Handbook of Computer Game Studies de Joost Raessens and Jeffrey Goldstein (LINK)

Video Games Around the World de Mark J. P. Wolf (LINK)

Computer Games and the Social Imaginary de Graeme Kirkpatrick (LINK)

Computer Games: Text, Narrative and Play de Diane Carr, David Buckingham, Andrew Burn e Gareth Schott (LINK)

Publicar na Steam

Surgiu na comunidade um relatório que foi desenvolvido a partir das respostas a questões por parte de pessoas que publicam ou publicaram na Steam.

Algumas das sugestões que são feitas estão relacionadas com:

“1. Remove ability for users to delete developers’ comments on their reviews.

2. Clarify what a developer needs to do in order to qualify for various featuring opportunities.

3. Bug reporting/technical support should be built into Steam/Steamworks. Filter issues that are Steam issues to Steam support team instead of to the developer.

4. Devs should be able to have one unified landing page for all their games.

5. The Steam Community feature needs better ways to deal with toxic users.

6. Valve should increase the overall volume of sustainable middle class developers.

7. Make reviews on the frontpage representative of the game’s review percentage.

8. The “Upcoming Games” list is becoming useless.

9. Devs should have better tools and info for tracking and identifying players who abuse/hack multiplayer, bot/farm item drops, etc.

10. Devs should have the possibility to send messages to forum users.

”

+infos(análise ao estudo): LINK

+infos(estudo completo): LINK

Livros a consumir (videojogos)

.2017

Metagaming Playing, Competing, Spectating, Cheating, Trading, Making, And Breaking Videogames de Stephanie Boluk e Patrick Lemieux

Fans And Videogames Histories, Fandom, Archives

.2016

A Lógica Do Jogo: Recriando Clássicos Da História Dos Videogames de Marcus Becker

How To Talk About Videogames de Ian, Prof. Bogost

Digital Games As History How Videogames Represent The Past And Offer Access To Historical Practice de Adam Chapman

Playback A Genealogy Of 1980s British Videogames de Alex Wade

.2015

Co-Creating Videogames de John Banks

.2014

Developer’S Dilemma The Secret World Of Videogame Creators de Casey O’Donnell

Videogames And Education de Harry J. Brown

.2013

Digital Games: A Context for Cognitive Development: New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, Number 139

.2011

The Videogames Handbook de James Newman, David Surman e Iain Simons

How To Do Things With Videogames de Ian Bogost

.2010

Persuasive Games The Expressive Power Of Videogames de Ian Bogost

.2009

Beyond Game Design Nine Steps Towards Creating Better Videogames de Chris Bateman

.2008

Studying Videogames de Wayne O’Brien e Julian Mcdougall

Playing With Videogames de James Newman

.2006

Game Writing Narrative Skills For Videogames de Chris Bateman

Computer Games: Text, Narrative and Play de Diane Carr, David Buckingham, Andrew Burn, Gareth Schott

Estudos sobre videojogos: um portal

Aqui está um portal que agrega alguns trabalhos relacionados com estudos feitos sobre os videojogos.

+infos: http://gamestudies.org/

revista: Entertainment Computing

Entertainment Computing publishes original, peer-reviewed research articles and serves as a forum for stimulating and disseminating innovative research ideas, emerging technologies, empirical investigations, state-of-the-art methods and tools in all aspects of digital entertainment, new media, entertainment computing, gaming, robotics, toys and applications among researchers, engineers, social scientists, artists and practitioners. Theoretical, technical, empirical, survey articles and case studies are all appropriate to the journal.

Specific areas of interest include:

• Computer, video, console and internet games

• Cultural computing and cultural issues in entertainment

• Digital new media for entertainment

• Entertainment robots and robot like applications

• Entertainment technology, applications, application program interfaces, and entertainment system architectures

• Human factors of entertainment technology

• Impact of entertainment technology on users and society

• Integration of interaction and multimedia capabilities in entertainment systems

• Interactive television and broadcasting

• Interactive art and entertainment

• Methodologies, paradigms, tools, and software/hardware architectures for supporting entertainment applications

• Mixed, augmented and virtual reality systems for entertainment

• New genres of entertainment technology

• Serious Games used in education, training, and research

• Simulation/gaming methodologies used in education, training, and research

• Social media for entertainment

In the area of empirical and experimental studies we are looking for contributions which are very well documented, innovative, and tested or evaluated in a particular entertainment domain.

+infos(revista): LINK